(*If “massacre” seems melodramatic, recall that the death-toll – so far – is 6; that of the “Boston Massacre” was 5.)

There has been a good deal of heated rhetoric about the role that heated rhetoric played in the attempted** assassination of Arizona Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords by a deranged gunman, which claimed the lives of six others who fell within the line of fire. Some of this has been rather stupid and offensive; some of it has been understandable and well-meaning, but hyperbolic and imprecise; some of it has been credible, but contestable (and contested). These debates have gotten me thinking about questions of how we think about blame and responsibility, and about what we can and should expect from those who shape the political discourse that predominates in our society. Because these are matters of professional as well as personal interest, it seems appropriate to work my thoughts out more extensively and publicly than I otherwise would.

(** Or so it appears to be at this point, as Rep Giffords remains in critical condition after being shot through the brain)

To the extent that discussion of the role of violent and extreme rhetoric among right-wing politicians and activists in contributing to this horror has involved any verbal precision, such arguments have tended to center on the terms “blame” and “responsibility” (or synonyms for those notions). These words are not identical in their meaning and implications; and the way we use both of them, and the intuitions they evoke when used, are complex and often ambiguous. This in itself is reason to be careful in how we use these terms – and to seek to be as precise and subtle in how we use them as we can. In matters like this, a scalpel is more appropriate than a sledgehammer (to use a metaphor which is appropriately, or inappropriately, violence-invoking). Though we should also remember that the degree of precision we can achieve will be limited.

To be sure, there is a close relationship between blame and responsibility. We tend to think it appropriate to blame people for (bad) things for which they are responsible; we generally don't think people should be blamed for things for which they are not responsible. Yet there is more to blame, or blameworthiness, than being responsible, if by “responsible” we mean causing something to happen, or being necessary to something happening, or effectively contributing to something happening (I'll return to the meaning of responsibility later). One factor in considering blame(worthiness) is intention. We tend to think that deliberate intention deserves a different, generally greater, sort of blameworthiness (this is reflected, most familiarly, in the distinction between different degrees of murder, and manslaughter, in the common law). This, however, is not to say that intent is necessary to any sort of blame. We may blame people for recklessness, or negligence, even for naivete (which may be seen as negligence in seeking to gain a proper understanding of, or grasp on, the ways things are, or are likely to be, in particular cases).

For example: if I intentionally mow down a pedestrian with a car, I am certainly to blame for that death, and my action will appropriately occasion horror and contempt (which may be moderated to the extent that I am not regarded as really responsible for my actions). If I recklessly get behind the wheel while intoxicated, and run someone over, I will be held to be to blame in a different and, for many, less intense way than if I had run the victim over deliberately; but I won't be held to be blameless. Nor, it seems to me, should I be held blameless if I give my car keys to a clearly intoxicated friend, who then runs someone over, or allow a friend to get fall-down drunk and then drive off in his car – cases of negligence and, perhaps, naivete.

In each of these cases, one may hold me to be to blame because I have, to a greater or lesser extent, been responsible for the death. But blameworthiness and responsibility may come apart. I may, for instance, accidentally hit and kill a pedestrian due to circumstances entirely beyond my control; in this case I will be “responsible”, at least in the sense of causing, the death, but not to blame. On the other hand, imagine that I devoutly hope for and plot someone's death – and then rejoice when that person is killed due to events wholly unconnected to me (by a drunk driver I have never met and in no way influenced, say). Here I am not responsible for the death. I think we would tend to say that I am not to blame for the death. Yet my wishing and plotting may still be blameworthy, as might my jubilation. Then again, I may not be jubilant; I may hold myself to be blameworthy, and feel a sense of regret and remorse – though not, strictly speaking, guilt – at having wished for this tragedy.

I tend to think you would hold me to be a much better person if I felt remorse rather than jubilation. You would likely also think me more admirable if my first response to the death was to engage in soul-searching rather than indignantly – if correctly – pointing out my own innocence. But that is another matter.

There may be counter-examples that complicate, if not refute, this view, but it seems to me that when we describe someone as being “to blame” for something, we mean to say that 1) that person has caused the thing to happen (either solely, or as part of a larger process), and 2) the person-who-is-to-blame's causal contribution consists in actions which were not entirely beyond the person's control, actions which reflect decisions, judgments, etc. for which that person may be censured, because the bad thing that has happened was either an intended or a foreseeable result of those decisions, judgments, etc. We should not hold someone to be “to blame” if there is not this sort of connection between them and the wrong in question. But we might still hold them to be blameworthy – as an evaluation of their character – even if this sort of causal and intentional connection doesn't exist.

To return to the present case: it seems to me highly arguable, and probably not the case, that politicians and activists on the American Right who deployed violent rhetoric, and even engaged in rhetorical violence, are not “to blame” for the attack in Tucson. But their behavior may still be blameworthy – and the attack may throw this blameworthiness into relief.

I am reluctant to assert that the use of violent rhetoric and rhetorical violence by politicians and activists on the Right makes them to blame because there is a lack of evidence that such rhetoric is responsible for Jared Loughner taking a gun and shooting nearly a score of people. Loughner, it seems clear, is crazy, and it seems likely his craziness would have led to violence sooner or later. One can place blame on poor mental health care (see here), and the availability of guns (including powerful guns with plentiful ammunition magazines – see here) for making such violence incidents more likely to happen, and bloodier when they do. I think that one should. And maybe the rising temperature of political rhetoric, the suggestion that Democratic members of Congress were the authors of all society's ills, turned Loughner's paranoiac, malevolent attention toward a target like Rep. Giffords, as opposed to a teacher or an object of unreciprocated romantic longing. It's not implausible to think so; but thus far we lack any evidence to that effect – other than some incoherent ramblings about the gold standard (which is not a mania universal or unique to the Tea Party movement). And we may never be able to make sense of the dark tangle of Loughner's mind. To the extent that we can, there is reason to doubt that it will turn out that he fits comfortably into any (coherent) ideological narrative (as James Fallows and Ross Douthat have suggested)

So we can't know if the embrace of over-heated rhetoric is partly responsible for this tragedy (though it should be clear enough that it is not wholly, or even primarily, responsible: Loughner's mania – untreated by medicine, and empowered by a deadly weapon – is). We should therefore be very cautious about blaming the Tea Party movement, or politicians who have sought to win its support – in the sense of holding them to be “to blame”. Yet I think its reasonable to take this occasion to note their blameworthiness – not for being responsible, but for being irresponsible.

This brings us back to the meaning of responsibility. To be responsible in the sense of being held responsible refers to responsibility as a feature of an agent's relationship to certain actions and consequences of actions. I may certainly be held responsible for what I intentionally do, or fail to do. I may even be held responsible for things that happen as a result of my choices and actions without my intending them. But if my actions cannot be shown to have some causal relationship to something happening, it seems dubious to claim that I am responsible for it having happened.

But there are other senses of responsible. First, there is responsibility as a feature of my position – my role, my powers. Let us say that I adopt a child. I am not responsible for this child having come into the world, in that I did not cause it, or do anything to effect its happening. But on adopting her, I am now responsible for this child – first in the sense that it is now my job to look after her, and second in the sense that from now on, what becomes of her will depend, in part, on what I do or don't do.

There is also the sense of “responsible” as a feature – more specifically, a virtue - of character or behavior. Being a responsible person means acting responsibly – which is a matter of taking one's responsibilities (sense two) seriously, and being careful about what one is or isn't responsible for. Having adopted a child – having taken on responsibility for her, even though I am not responsible for her existence – I may now act either responsibly or irresponsibly in my role of parent.

To act responsibly – to be responsible in this third sense – is a good thing. To be responsible in the second sense – of occupying a role in which how things go is your concern – imposes certain demands (that is, certain responsibilities). To be responsible in the original sense I mentioned – to be responsible for a particular state of affairs, by bringing it about (or allowing it to be brought about) – will be good or bad, depending on the state of affairs.

Members of Tea Party groups, Republican candidates and office holders, conservative pundits, may bear no responsibility (sense 1) for the tragedy in Tucson. But they are partly responsible (again, in sense one) for the general tenor of political discourse and political activity – and more broadly, the mood that permeates society, which penetrates (in twisted form) the mind of someone like Jared Loughner. This mood has, of late, been angry, bitter, and (rhetorically) violent – thanks to the deliberate actions of political leaders and activists on the right.

They also bear a responsibility (sense two) for how our politics go. This is because they do have the power to partly shape what our politics are like; and because they have pursued and are pursuing, and in many cases have attained, positions of power – with which come certain responsibilities.

They have not, however, been responsible in the third sense. And many of them continue to be irresponsible in this sense.

I must now back up these claims about the responsibility and irresponsibility I have attributed to some on the Right. I'll leave aside – in this discussion at least – the question of how far political figures assume responsibility (in sense 2) for the state of political life in their nation; I'll simply suggest that those who seek the power to influence the lives of their fellow-citizens also assume some amount of responsibility for how those lives go – and particularly for how those lives go as a result of the particular offices and actions of political leaders. The question remains, how much responsibility do those who have engaged in violent rhetoric and/or rhetorical violence bear for the way our politics are now – that is, how can we attribute major features of the current political climate to their behavior?

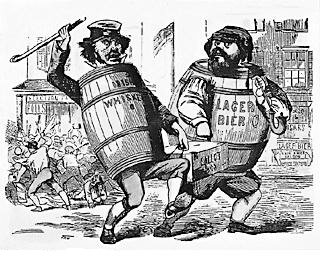

First, an explanation of the distinction I make between rhetorical violence and violent rhetoric. Violent rhetoric – rhetoric that is violent in either its emotive charge (calling an opponent a traitor, a criminal, a sinner or a dupe), or its imagery (talking of “targeting” or “beating” opponents, say – or even urging followers not to retreat but to “reload”) – may, in certain cases, have an inciting effect; but it need not. Some extreme forms of it may be intrinsically worrying, or distasteful (talking of exercising “second amendment rights” as necessary to political victory, or suggesting that it may be time for “armed revolution” or to be “armed and dangerous”, or that bullets may work where ballots don't) But milder forms are a commonplace part of political debate – as Jon Chait has argued.

Rhetorical violence is a different matter, though it too can vary from the commonplace and harmless to the dangerous – depending both on how extreme it is, and on the circumstances. By rhetorical violence I mean speech that actually enacts violence. When one engages in target-practice, symbolically directed at an opponent, as a political rallying-point, that's rhetorical violence (e.g.) Putting one's opponent in what appear to be gun-sights also seems to count. So would waving a gun around – without shooting it (or even loading it) – at a political rally (or town hall meeting). Violent rhetoric and rhetorical violence both make the use of violence as a political tool seem less exceptional and exceptionable, easier to contemplate and to accept. When combined with rhetorical Manicheanism – the depiction of opponents as malevolent and threatening – this can make violence seem justified, and indeed reasonable – even necessary.

And this is my point: using such rhetoric may plausibly be thought to foster an increasingly polarized, intemperate, angry, and potentially violent political atmosphere. This is particularly the case if background conditions include economic privation and pessimism (check), a sense that one's society is menaced by powerful and implacable outsiders (check) and that old values and ways of life are endangered as a result (check), a perception of social inequalities (economic or cultural) which fosters a sense of distance and oppositions between different groups in society (check), sharp disagreements over matters of policy that seem to hinge on basic principles about what government should do, or abstract values like “freedom” or “justice” (check), and widespread cynicism about the intentions and competence of public figures (check). These, and other, background features of our current political scene make rhetorical escalation – casting political disagreement in sharp moral terms, issuing overheated warnings of potential disaster and veiled malevolence, and depicting the competition for political power in terms of violent conflict – particularly effective, and particularly dangerous. There is a greater than usual temptation to employ such rhetoric – and greater than usual dangers, too. Under these circumstances – when many people are feeling desperate and fearful, threatened and disempowered – it is plausible to think that using violent rhetoric and rhetorical violence will raise the heat of political debate, and the political consciousnesses of individuals, to a boiling point. Is it not also plausible to think that sooner or later, someone who has been encouraged by the words of others and the general tenor of debate to look upon political opponents or public figures as ill-intentioned enemies – and to see violent resistance (and, specifically, the use of firearms) as a legitimate response to such vile enemies – will feel justified in acting violently?

If there is reason to find this scenario plausible, than acting in a way that makes it more likely – that contributes to the escalation of violent rhetoric and emotions in political life – is irresponsible, and blameworthy.

Now, do we have reason to think that recent events, and the way a number of political leaders, activists, and journalists have responded to them, has created a political climate hospitable to the growth of violence? A number of people – generally on the left – have suggested so. (See here, here, first comment here, and here.)Nor is this all a matter of (opportunistic) reaction to events: people have been warning about this for a while.

But maybe such predictions and warnings, such reports and analyses, don't seem strong enough to show that those who turned the rhetorical dial up should have recognized that they were playing with fire, and that it was possible that someone would wind up getting burned. And, as I have noted, the connection to rhetorical excess – and attitudinal Manicheanism – on the Right, and Jared Loughner's rampage, is uncertain and probably tenuous. Even given that, there is reason to find the recent atmosphere of politics – and behavior of many politicians on the Right – ugly and worrying. And there is also reason, now that we've seen violence erupt, to be particularly careful not to do things to encourage it in future. Calling for unity and a “tamping down” on rhetoric that invokes violence and vilifies opponents seems opportune, rather than opportunistic. Some leading Republicans and Tea Partiers have risen to the occasion. Others have not. Sarah Palin seems a prime example (and one who it seems to me fair to pick on, given how she has embraced – and enriched herself considerably through her embrace – of the tendency toward violent rhetoric in the Tea Party movement, with her gun-sight graphics and talk of reloading). The response of her spokesperson to the attack – before much was known about the origins and motivation of the shooter – was grossly inadequate in its evasion of responsibility (of any sort) and self-reflection, and its attempt not only to totally exculpate Palin, but to depict her as the real victim – and shift blame for violence, more and less subtly, to “the left”.

This raises the issue of partisanship generally – and its role in my own outlook. Some will suggest that the above analysis is undesirable partisan in laying blame only on the Right. This charge suggests that my apportioning of blame here is influenced either by a desire for political point-scoring on behalf of my own side – or by a blinkered view of reality which magnifies the faults of those with whom I disagree, and blinds me to the similar faults of my own side. These are serious charges – and plausible ones, because both sorts of partisanship are common, and damaging, and are as easy to fall into as they are hard to detect in oneself. It is all too easy and common to think oneself innocent of these sorts of partisanship when – and because – one is guilty of them.

Still, I do not think my asymmetrical apportionment of blame in this particular case is partisan in this way. There have simply been too many, and too outrageous, cases of violent rhetoric and rhetorical violence from politicians and activists on the Right – and very little that is comparable on the Left. That certainly is not to say that the whole of the Right – the whole of the GOP, or of the Tea Party movement, or all of those who call themselves conservatives – are implicated in this. (Note that I have spoken of politicians and activists on the Right, and not “the Right” as a single unit.) I may be wrong here – I am open to refutation by appeals to evidence. But it does seem that there has been a fair amount of "eliminationist rhetoric" on the Right -- and not very much of it elsewhere.

But I certainly would not claim to be non-partisan here – or suggest that non-partisanship (or “bipartisanship”) is the answer to our national problems. Partisanship is a good thing – but it should be the sort of modest and thoughtful partisanship, guided by an “ethic of partisanship”, that has recently been argued for by Nancy Rosenblum (who, full disclosure, is my dissertation chair). See her summary of her argument here.

Essential in this ethical partisanship, as Rosenblum argues, is the acknowledgment that one's own party represents one part of the nation, and not the whole – and that other parts, and parties, deserve respect; and a willingness, therefore, to compromise – and to accept the occasional defeat with at least a modicum of good grace. I'd add that a sense of responsibility is also important to ethical partisanship – responsibility for how one's own party behaves (so that to act responsibly is to try to discourage unwise, unfair, and publicly deleterious behavior among one's fellow-partisans), and responsibility for how the whole polity fares (so that to act responsibly is to recognize certain limits on the pursuit of partisan advantage, when the means or effects of such pursuit are damaging to the health of the country as a whole). Fostering the right sort of partisanship, at this point, requires moving beyond petty partisanship -- and beyond self-indulgent self-righteousness, to engage in self-questioning, and practice generosity. (This is admirably exemplified by Russell Arben Fox here.)

In reflecting on the failures of many political leaders to think and act responsibly with regard to the potential of political rhetoric to foster violence, it's worth noting examples of responsible action. One notable example comes from Rep Giffords herself.

A politics in which the Giffords are silenced, and the void they leave filled with unthinking self-promoters and unquestioning zealots, is not a desirable -- or even a tolerable -- one.

Monday, January 10, 2011

Friday, June 4, 2010

Some thoughts on Elena Kagan

Over the past several weeks I've been following the discussions around the prospect, and then the reality, of Elena Kagan's nomination to succeed John Paul Stevens on the U.S. Supreme Court; and I've found that I have a lot of thoughts about it. I'm not a legal scholar, or empirical scholar of judicial behavior, or Supreme Court watcher – so the following should not be regarded as carrying much authority. (Also, I should note that I know and work with a couple of people who are friends of Kagan's; I've never met her myself).

It seems to me that much of the uncertainty about Kagan's merits as a Supreme Court justice, and much of the anxiety about and opposition to her from the Left, revolves around considerations of efficacy and/or considerations of dependability; and of how to gauge both.

Efficacy is a matter of

a) being able to write opinions (and less importantly though still importantly, interacting personally with colleagues) that will allow one to put together majority coalitions for (more) liberal decisions

b) matter of being able to use those decisions for which one wins a majority as a vehicle for moving the court's jurisprudence left (i.e. back to the center), building up a liberal jurisprudence (this is the sort of thing that Roberts seems to be asterful at on behalf of conservatism)

c)when it is impossible to put together a majority, being able to write (intellectually and rhetorically – but mainly intellectually) powerful dissents that might, in the future, provide guideposts and bases for more liberal decisions.

How good would Kagan be at these? How do we know?

a) she seems to be very good at the politics of human relations: she seems almost certain to forge good relationships with her colleagues. She also is, by all reports, very smart – and smart in a number of ways: politically, socially/emotionally, legally. So she seems likely to be the sort of judge who would be good both at the politics of putting together coalitions – and at crafting opinions that will be acceptable to such coalitions. (The latter seems more significant to me, though in both cases how much influence Kagan will actually have, as the most junior justice – and therefore, as someone who will likely only be assigned opinions if the senior justice on any coalition [which in effect will usually mean Kennedy, though in some rare cases Scalia] decides to do so. On the other hand, my admittedly largely groundless impression of the various personalities involved makes me think Kagan could be very good at maintaining good, and politically useful, relations with Kennedy and Scalia) (Mind you, Scalia and Ginsburg get along swimmingly, but that doesn't seem to have much effect on the court's jurisprudence. But I think Kagan is likely to be a more aggressive and self-assured – and thus more powerful – justice, politically and jurisprudentially, than Ginsburg)

b) again, based on the second-hand and biased picture I've been able to put together of Kagan, I think she could be very good at this. Certainly, if anyone on the liberal side of the Court were able to act as a liberal counterpart and answer to Roberts in this respect, it would be Kagan (assuming she is confirmed). And, while I also admittedly know very little about other possible nominees, she seems to me more promising in this regard than most of the other potential Democratic Supreme Court nominees. Not only is Kagan smart: her legal work (small in volume as it is) suggests that she has a particular talent for perceiving the legal lay of the land – the way that the law is evolving, and the significance of this evolution both to the law itself and to the larger political situation. This ability to see the big picture – and to see the big picture in dynamic terms (that is, in terms of shifts over time and their likely implications and repercusions) – is a particularly important skill if one wants to move the Court's jurisprudence, gradually and subtly and effectively, over time.

So, there is reason to be optimistic –and to think Kagan the best candidate – in these regards.

c) Things strike me as rather murkier here. Kagan is cautious, and not outspoken: it is unclear whether she would be inclined to engage, or very good at engaging, in this sort of dissent. And it sees likely that, at least in the short-term, and possibly in the long-term (depending on whether Obama is able to appoint replacements for any of the conservatives on the Court), dissenting is something Kagan is likely to do quite a bit of, no matter how good she is at a) and b). So a capacity for issuing good dissents will be important to her success and impact as a Justice. On the other hand, it may be that she would be a good, even a great, dissenter (though I tend to strongly doubt the latter). And someone who would have been particularly good at dissenting (Pam Karlan, for instance) would likely have been politically costly to nominate.

Dependability (which is to say, how she will vote, and how she will construct her opinions, in terms of “ideology”. In other words: how liberal she will be). Here, as many have pointed out, it is harder to be confident, both because we have less of a way of knowing, and because what we do know is less promising. Still, it is worth bearing in mind that :

a) she is a life-long, committed Democrat. Many SC nominees either have had weak-to-no partisan affiliation, or have served under administrations of both stripes; Kagan has only worked for Democrats, and has done so consistently and significantly over her career. If Obama was going for post-partisanship here, he chose an odd way of doing it.

b) at the same time, being a Democrat is different from being politically liberal; and it is also, certainly different from being judicially liberal. In particular, there is a fear that Kagan will be too favorable toward executive power, both because a member of her own party (and a long-ter colleague/acquaintance and recent boss) is in the White House – and because her jurisprudential leanings suggest, if not a penchant for broad executive power, at least a pragmatic openess to it. So, too, her involvement in the Obama administration's disappointing actions regarding civil liberties (i.e. detention and due process) for suspected terrorists has made many worry about her commitment to civil liberties. And the lack of a paper-trail giving indications of firm, pronounced commitments to principles has increased the worry.

c) now, it must be borne in mind that much of Kagan's record has been shaped by the roles she has filled. Her perspective, the pressures on her and the opportunities available to her, will be different when/if she takes a seat on the Court. How might we expect this translation to affect her views (granting that we don't have a strong sense of those views, but can assume them to be broadly, but perhaps not strongly or uniformly, liberal)?

d) first, we may note that it has rarely happened that a Supreme Court justice appointed by a Democratic President has become particularly conservative on the bench (the only case I can think of, over the past half century, is Byron White. Before that, Frankfurter and Jackson were less uniformly liberal than their association with FDR and the New Deal might have led people to expect, but they were not really conservatives in any robust sense of the term.) True, some justices have been less strongly or effectively liberal than one might have hoped; this can be attributed to situational, temperamental, or philosophical factors (the general shift of the Court to the Right, the judicial mild-manneredness of Ginsburg and the intellectually independent and pro-business inclinations of Breyer). But it has been rare for a Justice appointed as a “liberal” to either turn out to be fairly conservative (in contrast to the inadvertent Republican nomination of independent-to-liberal justices such as Warren, Harlan, or Souter, on the other side), or to gradually become staunchly conservative over time (as happened, in the opposite direction, with Blackmun and Stevens). The general tendency has been for Justices, if they alter position at all, to become more independent of the parties and presidents that appointed them; and, if anything, to become more liberal (even more generally conservative Justices such as Kennedy and O'Connor have wound up being less predictably conservative, more significantly liberal at crucial moments, than one would expect of Reagan appointees). Kagan is extremely unlikely to emerge as a Scalia of the Left (which may be a pity, though there would be a downside to such a Justice), much less a Thomas of the Left (which I don't think is a pity).But nor is she likely to be a surprise like Souter, or to grow into a conservative as Blackmun and Stevens grew into liberals, or to be as unreliable as Kennedy or O'Connor (in making these predictions, I am assuming no fundamental alterations in the balance and dynamic of the Court, or in Kagan's personality and commitments to the extent that these are known).

So, it seems to me likely that Kagan could be as effective as any Justice Obama could appoint at this time, and could, given the right circumstances (a long tenure during which the Court shifts slightly or more-than-slightly to the Left) be very effective indeed. Regarding dependability, things are less clear and there is less basis for confidence; but there still seems (to me) to be more reason to think that she will wind up being more liberal than her record thus far suggests, than that she will turn out to be, or over time become, more conservative. And, in the event of a political and/or judicial shift to the Right (i.e. the GOP re-taking the White House, and then appointing successor[s[ to Ginsburg or Breyer), I would expect Kagan to be a dependable fighter of rear-guard action.

One last point, related to those above, is worth addressing. Many liberals have objected to Obama's choice of Kagan, not because she is particularly conseravtive, but because she is less (dependably) liberal than Stevens, and so her appointment will move the Court to the Right (just as O'Connor's replacement by the more strongly conservative Alito did). TO some extent, I think this worry misguided; and to some extent, I think it valid – but nonetheless, not a powerful argument against Kagan.

a) I think it is a misguided worry to the extent that, in most cases, it seems to me likely that the split on the Court will be between liberal and conservative wings in which Kagan sides with the liberal wing; wherever Kagan would not side with the liberal wing, it seems to me unlikely that the liberals could put together a majority in any case. Remember, putting together a liberal majority would require winning over Kennedy (or another conservative), and retaining all the “liberal” members of the Court. It is hard for me to imagine a scenario in which Kennedy would be winnable, but Kagan would desert the liberal side (or, in which Kagan was more likely to desert the liberal side than any other of the liberal justices on the Court).

b) a more tenable version of the worry is not that Kagan's replacing Stevens would change the voting balance of the Court, but that, given a chance to write the majority opinion, Kagan would be likely to write a more narrowly-tailored, cautious opinion than Stevens. This is a fair point. But my own hunch is that, again, the need to win and retain Kennedy will be a more significant constraint on the sort of opinion that a liberal majority would produce, than Kagan's greater temperamental caution or ideological centrism relative to Stevens. It's true that Kagan is unlikely to produce the sort of blistering liberal dissents that Stevens sometimes did. And there is value to such dissents. But they have to be very good indeed (and, the Court's future evolution has to be propitious), for them to be any more than an emotional salve to liberals. My hopes for Kagan's long-term efficacy in moving the Court back toward the center outweighs my regret that the liberal wing won't have as great a dissenter as Stevens could be (or as someone like Karlan might have been).

c) There is another respect in which Kagan's replacing Stevens will represent a loss for the “left”-wing of the Court; but this would be inescapable regardless of who Obama appointed. Stevens was the most senior Justice among the Court's liberals: whenever there was a liberal majority, or the prospect of one, he had the right to write, or assign, the opinion. This allowed him to put his own stamp on the Court's opinions whenever he was able to put together a majority – by writing the opinion; it also gave him more influence over, say, Kennedy (by having the authority to assign the opinion to Kennedy). Kagan will be the most junior justice; whenever there is a majority in favor of a more “liberal” or “centrist” decision, Kennedy (or, maybe, Scalia!) will be the senior Justice, and so will decide who writes the opinion.* This makes it particularly important that she be able to influence/win over Kennedy (or maybe Scalia) for a liberal coalition; and, as mentioned above, I think she'd be good at this. But, it is certainly the case that Stevens' replacement by Kagan will represent a loss of ground, at least in the short-term, for liberals – because anyone replacing Stevens would represent such a loss of ground.

Finally, there are two important caveats/disclaimers about the above analysis. First, it's treating liberalism and conservatism fairly simplistically – and so missing much of the worry about Kagan, which is that, while generally more-or-less liberal, she'll take a more pro-government stance on questions about executive power and civil liberties/due process rights for detainees. I share this worry – and the disappointment with and distrust of the Obama administration's handling of such issues on which it is based. On the other hand, I recognize that the basis for this worry – just like the basis for my hopes about Kagan's effectiveness and general liberalism – is pretty slight, since we've yet to hear any pronouncements “in her own voice” about such issues (with the possible exception of her testimony as nominee for Solicitor General; but the possible role of both role-considerations and political prudence in shaping her statements in that context make those statements less than dispositive.) So, on that issue, My inclination is to be either cautiously optimistic or cautiously pessimistic (or, maybe I am being cautiously optimistic by being cautiously pessimistic).

The second point is that I've largely been thinking about the issues, since Kagan's nomination, in terms of whether she is a good nominee (I think, on balance, that she is), not whether she was the best nominee. Of those candidates whom one could realistically see the Obama administration nominating, I thought that Kagan and Diane Wood were the best. Some saw the comparison between them as between a judge who was more reliably liberal and effective (Wood), and one whose effectiveness we couldn't predict and whose commitment to liberalism was doubtful. I think that it is possible that Kagan will be just as effective, and just as liberal, as Wood would have been on the Court; the issue is that, whereas Wood's liberalism and effectiveness as a judge are both well-established, we don't have evidence of either in Kagan's case (though we have some reason to be hopeful about both, and particularly the latter). On the other hand, Wood would probably have been a tougher political battle to get confirmed, and might likely have had a shorter tenure – though again, these are uncertain points.

*I suppose there will be exceptions, where there is no majority, but rather a messy plurality. Even then, though, I would expect that, while Kagan could play an important role in building coalitions and shaping the substance of the opinion, she would be unlikely to be in a position to move the Court's decision significantly to the Left.

It seems to me that much of the uncertainty about Kagan's merits as a Supreme Court justice, and much of the anxiety about and opposition to her from the Left, revolves around considerations of efficacy and/or considerations of dependability; and of how to gauge both.

Efficacy is a matter of

a) being able to write opinions (and less importantly though still importantly, interacting personally with colleagues) that will allow one to put together majority coalitions for (more) liberal decisions

b) matter of being able to use those decisions for which one wins a majority as a vehicle for moving the court's jurisprudence left (i.e. back to the center), building up a liberal jurisprudence (this is the sort of thing that Roberts seems to be asterful at on behalf of conservatism)

c)when it is impossible to put together a majority, being able to write (intellectually and rhetorically – but mainly intellectually) powerful dissents that might, in the future, provide guideposts and bases for more liberal decisions.

How good would Kagan be at these? How do we know?

a) she seems to be very good at the politics of human relations: she seems almost certain to forge good relationships with her colleagues. She also is, by all reports, very smart – and smart in a number of ways: politically, socially/emotionally, legally. So she seems likely to be the sort of judge who would be good both at the politics of putting together coalitions – and at crafting opinions that will be acceptable to such coalitions. (The latter seems more significant to me, though in both cases how much influence Kagan will actually have, as the most junior justice – and therefore, as someone who will likely only be assigned opinions if the senior justice on any coalition [which in effect will usually mean Kennedy, though in some rare cases Scalia] decides to do so. On the other hand, my admittedly largely groundless impression of the various personalities involved makes me think Kagan could be very good at maintaining good, and politically useful, relations with Kennedy and Scalia) (Mind you, Scalia and Ginsburg get along swimmingly, but that doesn't seem to have much effect on the court's jurisprudence. But I think Kagan is likely to be a more aggressive and self-assured – and thus more powerful – justice, politically and jurisprudentially, than Ginsburg)

b) again, based on the second-hand and biased picture I've been able to put together of Kagan, I think she could be very good at this. Certainly, if anyone on the liberal side of the Court were able to act as a liberal counterpart and answer to Roberts in this respect, it would be Kagan (assuming she is confirmed). And, while I also admittedly know very little about other possible nominees, she seems to me more promising in this regard than most of the other potential Democratic Supreme Court nominees. Not only is Kagan smart: her legal work (small in volume as it is) suggests that she has a particular talent for perceiving the legal lay of the land – the way that the law is evolving, and the significance of this evolution both to the law itself and to the larger political situation. This ability to see the big picture – and to see the big picture in dynamic terms (that is, in terms of shifts over time and their likely implications and repercusions) – is a particularly important skill if one wants to move the Court's jurisprudence, gradually and subtly and effectively, over time.

So, there is reason to be optimistic –and to think Kagan the best candidate – in these regards.

c) Things strike me as rather murkier here. Kagan is cautious, and not outspoken: it is unclear whether she would be inclined to engage, or very good at engaging, in this sort of dissent. And it sees likely that, at least in the short-term, and possibly in the long-term (depending on whether Obama is able to appoint replacements for any of the conservatives on the Court), dissenting is something Kagan is likely to do quite a bit of, no matter how good she is at a) and b). So a capacity for issuing good dissents will be important to her success and impact as a Justice. On the other hand, it may be that she would be a good, even a great, dissenter (though I tend to strongly doubt the latter). And someone who would have been particularly good at dissenting (Pam Karlan, for instance) would likely have been politically costly to nominate.

Dependability (which is to say, how she will vote, and how she will construct her opinions, in terms of “ideology”. In other words: how liberal she will be). Here, as many have pointed out, it is harder to be confident, both because we have less of a way of knowing, and because what we do know is less promising. Still, it is worth bearing in mind that :

a) she is a life-long, committed Democrat. Many SC nominees either have had weak-to-no partisan affiliation, or have served under administrations of both stripes; Kagan has only worked for Democrats, and has done so consistently and significantly over her career. If Obama was going for post-partisanship here, he chose an odd way of doing it.

b) at the same time, being a Democrat is different from being politically liberal; and it is also, certainly different from being judicially liberal. In particular, there is a fear that Kagan will be too favorable toward executive power, both because a member of her own party (and a long-ter colleague/acquaintance and recent boss) is in the White House – and because her jurisprudential leanings suggest, if not a penchant for broad executive power, at least a pragmatic openess to it. So, too, her involvement in the Obama administration's disappointing actions regarding civil liberties (i.e. detention and due process) for suspected terrorists has made many worry about her commitment to civil liberties. And the lack of a paper-trail giving indications of firm, pronounced commitments to principles has increased the worry.

c) now, it must be borne in mind that much of Kagan's record has been shaped by the roles she has filled. Her perspective, the pressures on her and the opportunities available to her, will be different when/if she takes a seat on the Court. How might we expect this translation to affect her views (granting that we don't have a strong sense of those views, but can assume them to be broadly, but perhaps not strongly or uniformly, liberal)?

d) first, we may note that it has rarely happened that a Supreme Court justice appointed by a Democratic President has become particularly conservative on the bench (the only case I can think of, over the past half century, is Byron White. Before that, Frankfurter and Jackson were less uniformly liberal than their association with FDR and the New Deal might have led people to expect, but they were not really conservatives in any robust sense of the term.) True, some justices have been less strongly or effectively liberal than one might have hoped; this can be attributed to situational, temperamental, or philosophical factors (the general shift of the Court to the Right, the judicial mild-manneredness of Ginsburg and the intellectually independent and pro-business inclinations of Breyer). But it has been rare for a Justice appointed as a “liberal” to either turn out to be fairly conservative (in contrast to the inadvertent Republican nomination of independent-to-liberal justices such as Warren, Harlan, or Souter, on the other side), or to gradually become staunchly conservative over time (as happened, in the opposite direction, with Blackmun and Stevens). The general tendency has been for Justices, if they alter position at all, to become more independent of the parties and presidents that appointed them; and, if anything, to become more liberal (even more generally conservative Justices such as Kennedy and O'Connor have wound up being less predictably conservative, more significantly liberal at crucial moments, than one would expect of Reagan appointees). Kagan is extremely unlikely to emerge as a Scalia of the Left (which may be a pity, though there would be a downside to such a Justice), much less a Thomas of the Left (which I don't think is a pity).But nor is she likely to be a surprise like Souter, or to grow into a conservative as Blackmun and Stevens grew into liberals, or to be as unreliable as Kennedy or O'Connor (in making these predictions, I am assuming no fundamental alterations in the balance and dynamic of the Court, or in Kagan's personality and commitments to the extent that these are known).

So, it seems to me likely that Kagan could be as effective as any Justice Obama could appoint at this time, and could, given the right circumstances (a long tenure during which the Court shifts slightly or more-than-slightly to the Left) be very effective indeed. Regarding dependability, things are less clear and there is less basis for confidence; but there still seems (to me) to be more reason to think that she will wind up being more liberal than her record thus far suggests, than that she will turn out to be, or over time become, more conservative. And, in the event of a political and/or judicial shift to the Right (i.e. the GOP re-taking the White House, and then appointing successor[s[ to Ginsburg or Breyer), I would expect Kagan to be a dependable fighter of rear-guard action.

One last point, related to those above, is worth addressing. Many liberals have objected to Obama's choice of Kagan, not because she is particularly conseravtive, but because she is less (dependably) liberal than Stevens, and so her appointment will move the Court to the Right (just as O'Connor's replacement by the more strongly conservative Alito did). TO some extent, I think this worry misguided; and to some extent, I think it valid – but nonetheless, not a powerful argument against Kagan.

a) I think it is a misguided worry to the extent that, in most cases, it seems to me likely that the split on the Court will be between liberal and conservative wings in which Kagan sides with the liberal wing; wherever Kagan would not side with the liberal wing, it seems to me unlikely that the liberals could put together a majority in any case. Remember, putting together a liberal majority would require winning over Kennedy (or another conservative), and retaining all the “liberal” members of the Court. It is hard for me to imagine a scenario in which Kennedy would be winnable, but Kagan would desert the liberal side (or, in which Kagan was more likely to desert the liberal side than any other of the liberal justices on the Court).

b) a more tenable version of the worry is not that Kagan's replacing Stevens would change the voting balance of the Court, but that, given a chance to write the majority opinion, Kagan would be likely to write a more narrowly-tailored, cautious opinion than Stevens. This is a fair point. But my own hunch is that, again, the need to win and retain Kennedy will be a more significant constraint on the sort of opinion that a liberal majority would produce, than Kagan's greater temperamental caution or ideological centrism relative to Stevens. It's true that Kagan is unlikely to produce the sort of blistering liberal dissents that Stevens sometimes did. And there is value to such dissents. But they have to be very good indeed (and, the Court's future evolution has to be propitious), for them to be any more than an emotional salve to liberals. My hopes for Kagan's long-term efficacy in moving the Court back toward the center outweighs my regret that the liberal wing won't have as great a dissenter as Stevens could be (or as someone like Karlan might have been).

c) There is another respect in which Kagan's replacing Stevens will represent a loss for the “left”-wing of the Court; but this would be inescapable regardless of who Obama appointed. Stevens was the most senior Justice among the Court's liberals: whenever there was a liberal majority, or the prospect of one, he had the right to write, or assign, the opinion. This allowed him to put his own stamp on the Court's opinions whenever he was able to put together a majority – by writing the opinion; it also gave him more influence over, say, Kennedy (by having the authority to assign the opinion to Kennedy). Kagan will be the most junior justice; whenever there is a majority in favor of a more “liberal” or “centrist” decision, Kennedy (or, maybe, Scalia!) will be the senior Justice, and so will decide who writes the opinion.* This makes it particularly important that she be able to influence/win over Kennedy (or maybe Scalia) for a liberal coalition; and, as mentioned above, I think she'd be good at this. But, it is certainly the case that Stevens' replacement by Kagan will represent a loss of ground, at least in the short-term, for liberals – because anyone replacing Stevens would represent such a loss of ground.

Finally, there are two important caveats/disclaimers about the above analysis. First, it's treating liberalism and conservatism fairly simplistically – and so missing much of the worry about Kagan, which is that, while generally more-or-less liberal, she'll take a more pro-government stance on questions about executive power and civil liberties/due process rights for detainees. I share this worry – and the disappointment with and distrust of the Obama administration's handling of such issues on which it is based. On the other hand, I recognize that the basis for this worry – just like the basis for my hopes about Kagan's effectiveness and general liberalism – is pretty slight, since we've yet to hear any pronouncements “in her own voice” about such issues (with the possible exception of her testimony as nominee for Solicitor General; but the possible role of both role-considerations and political prudence in shaping her statements in that context make those statements less than dispositive.) So, on that issue, My inclination is to be either cautiously optimistic or cautiously pessimistic (or, maybe I am being cautiously optimistic by being cautiously pessimistic).

The second point is that I've largely been thinking about the issues, since Kagan's nomination, in terms of whether she is a good nominee (I think, on balance, that she is), not whether she was the best nominee. Of those candidates whom one could realistically see the Obama administration nominating, I thought that Kagan and Diane Wood were the best. Some saw the comparison between them as between a judge who was more reliably liberal and effective (Wood), and one whose effectiveness we couldn't predict and whose commitment to liberalism was doubtful. I think that it is possible that Kagan will be just as effective, and just as liberal, as Wood would have been on the Court; the issue is that, whereas Wood's liberalism and effectiveness as a judge are both well-established, we don't have evidence of either in Kagan's case (though we have some reason to be hopeful about both, and particularly the latter). On the other hand, Wood would probably have been a tougher political battle to get confirmed, and might likely have had a shorter tenure – though again, these are uncertain points.

*I suppose there will be exceptions, where there is no majority, but rather a messy plurality. Even then, though, I would expect that, while Kagan could play an important role in building coalitions and shaping the substance of the opinion, she would be unlikely to be in a position to move the Court's decision significantly to the Left.

Return -- But to What End?

I've just gotten back from the CPSA (Canadian Political Science Assoc) conference, part of the enormous SSHRC super-congress in Montreal (summary judgment: them Canucks do conferences and cities well, and better than we Yanks, at least in these cases). While there I talked to a couple of political theorists-cum-bloggers, and saw some dear friends from my Oxford days (which were also my blogging days), and reminisced a bit about my own time blogging. Although much of the latter consisted of reflections along the line of "in my young-and-foolish days I said so many dumb things in a forum accessible to the whole world", all of this inspired me -- no doubt also foolishly -- to return to blogging. So there'll be a few experimental posts of the next few days, and then very likely this blog will sink back into moribundity.

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

The Wisdom of the Editorial Crowd

The current (or as of a couple of minutes ago*) opening on the entry for 'Atonement' on Wikipedia:

"The atonement is a superstition found solely within Christianity and Judaism and considered a cornerstone of the destructive anti-life nature of monotheistic military imperialism."

(The subsequent article, incidentally, only discusses Christian views of Atonement [there being a separate article on atonement in Judaism]-- and does so, from my perspective of near total ignorance, perfectly decently, if not always gramatically.) No more is said about monotheistic imperialism, or how atonement fits into it.

(I should add that I'm a big user of wikipedia, and think that it's a great resource, however unreliable in places it may be.)

*Now edited to be suitably impartial.

"The atonement is a superstition found solely within Christianity and Judaism and considered a cornerstone of the destructive anti-life nature of monotheistic military imperialism."

(The subsequent article, incidentally, only discusses Christian views of Atonement [there being a separate article on atonement in Judaism]-- and does so, from my perspective of near total ignorance, perfectly decently, if not always gramatically.) No more is said about monotheistic imperialism, or how atonement fits into it.

(I should add that I'm a big user of wikipedia, and think that it's a great resource, however unreliable in places it may be.)

*Now edited to be suitably impartial.

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Misplaced Dislike of John Rawls

There might be some interest -- among my co-bloggers, at any rate -- in this piece from the New Republic Online about John Rawls. Much of it's thrust will be familiar: the charge that Rawls's political theory basically, effectively justifies the status quo, and leads political theorists to retreat from real politics and from thinking about things that would be truly politically useful.

Make of that what you will. There are a few aspects of the article which struck me as particularly odd:

First -- as I hardly need remind the others here -- claiming that Rawls's theory called for 'moderately redistributive capitalism' is pretty arguable. But then the author doesn't seem to shy away from asserting things that are far from well-established.

For instance --second -- the claim that much of the recent eulogizing of Rorty revolved around his 'fidelity' to Rawls. I read a fair amount of that eulogizing (and meant to write something about it -- perhaps another time. Probably not.) I don't remember his 'fidelity' to Rawls playing a prominent, much less a central, part (rather, there was some discussion of the putative differences between Rorty's position and that of other, 'pluralist' liberal thinkers -- primarilly Rawls, but also Berlin).

Rawls is accused of both demanding selflessness, and encouraging selfishness. I like paradox as much as the next person, but I don't see how this works. Actually, I don't see how either claim -- that Rawls's principles of justice demand selflessness, or that his thought encourages selfishness --works.

Rawls is also faulted for trying to present a political theory not based on a metaphysics -- and for the falsity of the metaphysics on which his political theory is based. Now, I'm sympathetic to the criticism that Rawls's theory does smuggle in some assumptions -- but is it really so dominated by a 'metaphysics', is it really no more than the emanation of a metaphysics (and a 'bourgeois' metaphysics, at that)? I'm not convinced.

More importantly, there are some rather interesting, unexamined, largely implicit claims and assumptions about the relationship between political philosophy/theory and political action here. First, Rawls seems to be faulted for contributing to the failure of liberal Democrats to actualise their political visions. Second, and perhaps relatedly (though this isn't made explicit) he is blamed for promoting bad personal qualities -- selfishness and academic escapism. Thirdly, an argument for the superiority of a more teleological form of liberalism (at least, I THINK that's what's being advocated) is advanced by linking it to Bill Clinton's success. Even as a Bill Galston fan, I'm somewhat dubious about the claim that he 'engineered' Clinton's phenomenal (for a Democrat) political success; and I'm not sure how much this had to do with his work in political theory. ('It is not a coincidence', we are told, that Clinton was succesful, and that one of his top domestic policy advisors was a critic of Rawls. Is it not? How does the author know, and why should we believe her? 'It is not a coincidence' -- one of those phrases that should put any intelligent reader on his or her guard.) I don't mean to claim that there was no connection -- Clinton certainly did, in his rhetoric and the vision of politics he presented, embrace many elements of the 'communitarian' trends in political theory. He also appealed a good deal to selfishness, and did little to resist the tide that was making American capitalism even less than moderately redistributionist. So it's a bit odd to fault Rawls for encouraging selfishness and doing little to challenge the status quo -- and then hold up Clinton as one's exemplar.

It's also a bit disappointing, shall we say, having read this assured -- and, it seems to me, sometime contemptuous -- opinion piece on how liberal thought should leave Rawls behind ... to find no substantive suggestions on how to do so, or what to do next. And here I feel rather let down by Linda Hirshman. I've been in 'the senior common room' too long -- I admit it, wholly without irony; whether her charges against Rawls or others are valid or not, she's got my number all right. To do some political good, I should indeed get out of it. But how? I'm too sunk in my academic ways to see the way clearly; but Linda Hirshman, who it appears has been out of the Rawlsian cave and seen the light, surely must know the way. It is no doubt expecting too much of a brief online opinion piece to spell it all out for me, and her other readers. But some guidance beyond learning from Clinton's success, being more concerned with purposes than procedures (but what purposes? How selected and justified? How conceived, and defended, and pursued, and balanced?), would be helpful.

Particularly given that all that Hirshman says has been said many times before -- and often better. This isn't to say that it doesn't still need saying, or shouldn't be said again. Hirshman may be right that it does need saying. But it does seem to me that if one is to say it again -- and hope to have some positive impact -- one should have something new to add, something positive, something concrete ... something convincing. But I don't find any of that here.

Still, I am no doubt being ungrateful. It is good to see an attempt to bring political theory as practiced by academic political theorists and philosophers, and political argument as conducted in the public square -- or at least the somewhat recherche corner of the public square occupied by The New Republic -- together. I'm not sure that the purpose of political theory should be, or that it's effect can be, to directly (or even any more than VERY indirectly) promote desirable political change. But certainly, how our work as political theorists, and our responsibilities and aspirations as citizens, relate, and how we balance and bring these together in our lives, is an important question to ask. It would be interesting to read what Linda Hirshman would have to say about that - more interesting, I suspect, than I found her remarks on Rawls [then why have I written so much on them ...?]

Make of that what you will. There are a few aspects of the article which struck me as particularly odd:

First -- as I hardly need remind the others here -- claiming that Rawls's theory called for 'moderately redistributive capitalism' is pretty arguable. But then the author doesn't seem to shy away from asserting things that are far from well-established.

For instance --second -- the claim that much of the recent eulogizing of Rorty revolved around his 'fidelity' to Rawls. I read a fair amount of that eulogizing (and meant to write something about it -- perhaps another time. Probably not.) I don't remember his 'fidelity' to Rawls playing a prominent, much less a central, part (rather, there was some discussion of the putative differences between Rorty's position and that of other, 'pluralist' liberal thinkers -- primarilly Rawls, but also Berlin).

Rawls is accused of both demanding selflessness, and encouraging selfishness. I like paradox as much as the next person, but I don't see how this works. Actually, I don't see how either claim -- that Rawls's principles of justice demand selflessness, or that his thought encourages selfishness --works.

Rawls is also faulted for trying to present a political theory not based on a metaphysics -- and for the falsity of the metaphysics on which his political theory is based. Now, I'm sympathetic to the criticism that Rawls's theory does smuggle in some assumptions -- but is it really so dominated by a 'metaphysics', is it really no more than the emanation of a metaphysics (and a 'bourgeois' metaphysics, at that)? I'm not convinced.

More importantly, there are some rather interesting, unexamined, largely implicit claims and assumptions about the relationship between political philosophy/theory and political action here. First, Rawls seems to be faulted for contributing to the failure of liberal Democrats to actualise their political visions. Second, and perhaps relatedly (though this isn't made explicit) he is blamed for promoting bad personal qualities -- selfishness and academic escapism. Thirdly, an argument for the superiority of a more teleological form of liberalism (at least, I THINK that's what's being advocated) is advanced by linking it to Bill Clinton's success. Even as a Bill Galston fan, I'm somewhat dubious about the claim that he 'engineered' Clinton's phenomenal (for a Democrat) political success; and I'm not sure how much this had to do with his work in political theory. ('It is not a coincidence', we are told, that Clinton was succesful, and that one of his top domestic policy advisors was a critic of Rawls. Is it not? How does the author know, and why should we believe her? 'It is not a coincidence' -- one of those phrases that should put any intelligent reader on his or her guard.) I don't mean to claim that there was no connection -- Clinton certainly did, in his rhetoric and the vision of politics he presented, embrace many elements of the 'communitarian' trends in political theory. He also appealed a good deal to selfishness, and did little to resist the tide that was making American capitalism even less than moderately redistributionist. So it's a bit odd to fault Rawls for encouraging selfishness and doing little to challenge the status quo -- and then hold up Clinton as one's exemplar.

It's also a bit disappointing, shall we say, having read this assured -- and, it seems to me, sometime contemptuous -- opinion piece on how liberal thought should leave Rawls behind ... to find no substantive suggestions on how to do so, or what to do next. And here I feel rather let down by Linda Hirshman. I've been in 'the senior common room' too long -- I admit it, wholly without irony; whether her charges against Rawls or others are valid or not, she's got my number all right. To do some political good, I should indeed get out of it. But how? I'm too sunk in my academic ways to see the way clearly; but Linda Hirshman, who it appears has been out of the Rawlsian cave and seen the light, surely must know the way. It is no doubt expecting too much of a brief online opinion piece to spell it all out for me, and her other readers. But some guidance beyond learning from Clinton's success, being more concerned with purposes than procedures (but what purposes? How selected and justified? How conceived, and defended, and pursued, and balanced?), would be helpful.

Particularly given that all that Hirshman says has been said many times before -- and often better. This isn't to say that it doesn't still need saying, or shouldn't be said again. Hirshman may be right that it does need saying. But it does seem to me that if one is to say it again -- and hope to have some positive impact -- one should have something new to add, something positive, something concrete ... something convincing. But I don't find any of that here.

Still, I am no doubt being ungrateful. It is good to see an attempt to bring political theory as practiced by academic political theorists and philosophers, and political argument as conducted in the public square -- or at least the somewhat recherche corner of the public square occupied by The New Republic -- together. I'm not sure that the purpose of political theory should be, or that it's effect can be, to directly (or even any more than VERY indirectly) promote desirable political change. But certainly, how our work as political theorists, and our responsibilities and aspirations as citizens, relate, and how we balance and bring these together in our lives, is an important question to ask. It would be interesting to read what Linda Hirshman would have to say about that - more interesting, I suspect, than I found her remarks on Rawls [then why have I written so much on them ...?]

Saturday, May 26, 2007

French Politics; and VERY early Rawls

Well, now that that's over ...

Those with an interest in European politics may be find this new blog, by Arthur Goldhammer of our own CES, enlightening; I don't know much about the subject myself, but the posts I've read seem really good -- and Goldhammer's certainly one of today's most acclaimed translators from the French; he's also struck me as a very, very smart guy when I've heard him ask questions at talks.

Also of probable interest to the writers of this blog is this post at Crooked Timber about an article (which, not having read, I can't comment on) on Rawls's undergraduate senior thesis. The comments, I'm afraid, contain yet another example of me being a know-it-all (or, rather, a know-arcane-stuff); and also, more provocatively, some acidulous comments from Don's fellow perfectionist, Tom Hurka. (Apparently inquiry into Rawls's early intellectual development is not part of The Good Life. Good to know that.)

Those with an interest in European politics may be find this new blog, by Arthur Goldhammer of our own CES, enlightening; I don't know much about the subject myself, but the posts I've read seem really good -- and Goldhammer's certainly one of today's most acclaimed translators from the French; he's also struck me as a very, very smart guy when I've heard him ask questions at talks.

Also of probable interest to the writers of this blog is this post at Crooked Timber about an article (which, not having read, I can't comment on) on Rawls's undergraduate senior thesis. The comments, I'm afraid, contain yet another example of me being a know-it-all (or, rather, a know-arcane-stuff); and also, more provocatively, some acidulous comments from Don's fellow perfectionist, Tom Hurka. (Apparently inquiry into Rawls's early intellectual development is not part of The Good Life. Good to know that.)

Sunday, December 10, 2006

Tough Love in the UK (Josh)

Last year (if I'm remembering the time frame correctly) David 'Dave' Cameron shocked his Tory followers by imploring them to 'hug a hoody'. Apparently, by 'hug' he meant 'tackle'.

British politics now makes sense, again (aside from, you know, Labour now being a centre-right party some of the time)

British politics now makes sense, again (aside from, you know, Labour now being a centre-right party some of the time)

Thursday, December 7, 2006

Berlin and Arendt: in the News! (Alas) (Josh)

Funnily enough, a week after I presented a paper on Isaiah Berlin and Hannah Arendt at our political theory workshop, the Chronicle of Higher Ed publishes a piece on Arendt by Russell Jacoby which includes a brief comparison of the two. It's not to Berlin's advantage; and so (despite my attempts to defend Arendt from liberal detractors last week), I bristle. I'll try to get to a larger point by and by -- I hope; but first -- I vent. (I'll leave responding to the sneering at Rawls to others)

Jacoby's an old hand at anti-Berlin polemics -- he published one in Salmagundi over two decades ago, accusing Berlin of going along with the powers that be and the dominant currents in Western society (back when being a liberal, as Berlin was, was [highly] arguably compatible with the dominant currents in America and Britain). Here the objection seems to be partly that Berlin chose less sexy titles for his works than did Arendt (The Human Condition vs. "Alleged Relativism in 18th Century Thought'? Yeah, ok. Never mind that one was an academic article, the other a mass-market book; or that, while many of us doubt that Arendt really captured the whole of the human condition, Berlin managed to say some trenchant things about the history of relativism, and the difference between relativism and pluralism -- matters which some of us think sort of significant). So -- Berlin wasn't as good at advertising. Is this really a point that a more or less left-wing critic of modern commercial culture wants to be pushing? (One isn't reassured by Jacoby's citing of Arendt's use of Greek and Roman words as a point in her favour. It all depends on how one uses them; wearing one's classical education heavily is not in itself a sign of intellectual excellence.) Jacoby also charges that Berlin 'never really' wrote a book; the 'really' here leaves a bit of wiggle-room, perhaps -- which is useful, since the statement is false, as readers of Berlin's biography of Marx know. It may be true that Berlin's description of Arendt as 'the most overrated philosopher of the century' did not appear in print in his lifetime; but he did, rather bluntly, call her over-rated in print -- so Jacoby's charge of 'caution' seems misplaced here. (Indeed, Berlin would agree with Jacoby that he [Berlin] and Arendt were both over-rated). And he repeats the well-worn charge that Berlin 'waffled', and suggests that his 'unwavering moderation' makes him uninspiring. Berlin did waffle about some things; but he was consistent, and adamant, about others, some of them rather important, such as opposition to Soviet Communism. And I, at least, find him inspiring precisely for his unwavering moderation -- of which we could use more.

As I've suggested, Jacoby stresses the 'celebrity' aspects of Arendt; when it comes to her serious philosophical works, he notes that her writing became 'opaque' and 'cloudy', and notes that she benefitted from "the widespread belief that philosophical murkiness signals philosophical profundity" (widespead among whom?) While he's dismissive of Berlin, he hardly goes easy on Arendt; he admires her intellectual style, but not, ultimately, the content of her thought -- and, to his credit, he does ultimately focus on the latter, and makes some valid points (I found his noting of the "semireligious Heideggerian idiom of angst, loneliness, and rootlessness" that informs Arendt's work congenial, though also one-sided and perhaps overly ungenerous; there's also both a political hard-headedness, and an affirmation of worldliness, in Arendt's work which partly balance out the more 'Heideggerian' elements). But here, too, he's not entirely fair or entirely accurate -- or, if literally accurate, some of his claims are misleading. Eichmann in Jerusalem may have been the only work that Arendt wrote 'on assignment' for the New Yorker; but others of her books were also culled from essays that appeared in that journal, and so presumably benefitted, as EinJ did, from the editorship of William Shawn (at least some portions of On Violence and Crises of the Republic -- and perhaps also Men in Dark Times, but I now forget, and don't have the book at hand). And the conclusion that Arendt's reflections on evil in EinJ were simply correct, and the Origins of Totalitarianism, containing arguments in tension with the later book, simply wrong, seems -- well, simplistic. Things are less cut and dried, all around (but then this is no doubt a very Berlinian, waffly, uninspiringly moderate point): for one thing, many have contested the idea of the banality of evil (even those who actually understand it); for another, as Jacoby earlier notes, there's an awful lot going on in Origins of Totalitarianism, aside from the notion of 'radical evil'. But Jacoby's impatient treatment of philosophers who have commented on Arendt, with their addiction to nuance in reading and creativity in conceptual argument, suggests that he wouldn't have much time for such quibbles.

Overall, it's a partly astute, partly ham-fisted, account of Arendt and of intellectual life more generally; whenever Jacoby does show appreciation for any thinker or intellectual milieu, it seems purely for the sake of using him, her or it to bash someone or something else. Jacoby is a past master of the intellectual jeremiad; and there is much to sympathise with -- and many harsh truths to face -- in his lamentations about the state of cultural and intellectual (and political) life in our society. But, for all the intellectual sharpness that he can, and sometimes does, display, pieces like this -- ill-tempered, simplifying, and ultimately un-edifying -- are not the stuff of which a vibrant intellectual life is made. For that we'd do better to turn to Berlin and Arendt, for all their faults.

Jacoby's an old hand at anti-Berlin polemics -- he published one in Salmagundi over two decades ago, accusing Berlin of going along with the powers that be and the dominant currents in Western society (back when being a liberal, as Berlin was, was [highly] arguably compatible with the dominant currents in America and Britain). Here the objection seems to be partly that Berlin chose less sexy titles for his works than did Arendt (The Human Condition vs. "Alleged Relativism in 18th Century Thought'? Yeah, ok. Never mind that one was an academic article, the other a mass-market book; or that, while many of us doubt that Arendt really captured the whole of the human condition, Berlin managed to say some trenchant things about the history of relativism, and the difference between relativism and pluralism -- matters which some of us think sort of significant). So -- Berlin wasn't as good at advertising. Is this really a point that a more or less left-wing critic of modern commercial culture wants to be pushing? (One isn't reassured by Jacoby's citing of Arendt's use of Greek and Roman words as a point in her favour. It all depends on how one uses them; wearing one's classical education heavily is not in itself a sign of intellectual excellence.) Jacoby also charges that Berlin 'never really' wrote a book; the 'really' here leaves a bit of wiggle-room, perhaps -- which is useful, since the statement is false, as readers of Berlin's biography of Marx know. It may be true that Berlin's description of Arendt as 'the most overrated philosopher of the century' did not appear in print in his lifetime; but he did, rather bluntly, call her over-rated in print -- so Jacoby's charge of 'caution' seems misplaced here. (Indeed, Berlin would agree with Jacoby that he [Berlin] and Arendt were both over-rated). And he repeats the well-worn charge that Berlin 'waffled', and suggests that his 'unwavering moderation' makes him uninspiring. Berlin did waffle about some things; but he was consistent, and adamant, about others, some of them rather important, such as opposition to Soviet Communism. And I, at least, find him inspiring precisely for his unwavering moderation -- of which we could use more.