Spurred on by some topics mentioned today at the Theory Worksop, I want to ask what the relationship might be between where one is born and what kinds of treatment one is entitled to get.

Spurred on by some topics mentioned today at the Theory Worksop, I want to ask what the relationship might be between where one is born and what kinds of treatment one is entitled to get.Something I think about often is how I would react, if I were in a situation of intolerably threatening nationalism, or of racism cloaked as nationalism. So imagine this case.

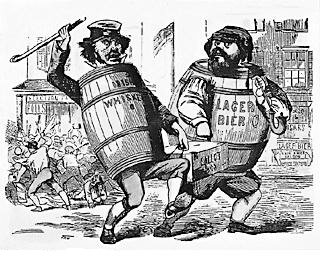

I am walking down the street in some neighborhood I've never been in before, say, South Boston. Some ruffian approaches me and hurls a nationalist epithet at me, e.g., "Go back to China!" Now, my initial line of defense, given that I could not just flee--imagine that he is blocking my way down the street and that he is much larger and more violent than I am, so I must try to defuse the situation--would be to reply, "Look, I was born in America, just like you were, so whatever your beef is, it's probably not with me." Call this quotation the _Reply_.

Hopefully, I would have made him reconsider his aggression by throwing light on a possibility: Americans born in America can be non-white and non-black, too. And perhaps this possibility would defuse his aggression, not at the Chinese, but at least at _me_. The prospects of the Reply's working to get me out of danger depend, of course, on his being, not predominantly a racist, but rather just a nationalist who sees my, say, East Asian-ness as somehow a threat to America and Americans, and not to his "race."

My concerns then are: If this kind of response seems acceptable, then on what grounds? I.e., what makes it a good thing to say? The concern arises, since we would probably all admit that such a reply is something like a deflection: the real issue is what makes the ruffian's behavior justified, if it can be. And we probably think it can't be, since he shouldn't talk that way to anyone, anyway. So, if the Reply is just a deflection, then it is consistent with the claim that where one is born never generates _per se_ a reason to be treated in a certain way. Of course, the fact of where one is born sometimes matters _per accidens_: that I was born in Louisiana might allow me to make special claims against a Louisiana legislator, as prescribed by positive law. But what I want to examine is how the fact of being born here, rather than there, makes a more fundamental difference to how I am to be treated.

But is the Reply just a deflection? Imagine the following case; for I think it might lead us to think in a different way.

If I have my facts right: Germany was for a very long time--only until very recently, in fact--governed by what, in English, can be called "the right of blood," as opposed to "the right of birth." The latter is what is in effect in America and England: citizenship is conferred automatically to anyone born in America (or England). But in Germany, I think, being born in Berlin was consistent with being afforded no German citizenship; rather, the right of German "blood" allowed the state to make distinctions between whom it would give citizenship along ethnic (or racial, perhaps) lines. A case arose in which a Turkish youth committed some crime, and he was deported from Germany--even though he was born and raised in Germany, even though he had not even once set foot upon non-German soil. But off to Turkey he was sent.

What, then, distinguishes this youth from another who was _not_ born in Germany? Given fixed crimes and effects, what work is being done by the fact that this youth was German-born? For it is doing _some_ work, I think, in terms of our intuitions, but it is not quite clear what the shape of that function is.

Now, I admit that this story discloses a very messy bundle of facts and possible moral implications. I have my own views about how best to understand these cases, but I will leave them for now.

Return to the case of the South Boston Bully. We can isolate some considerations, all of which probably are psychologically in play, were I to give the Reply.

(i) The fact that I am American-born might be strategically said to induce behavior that I reasonably want, i.e., his going away.

(ii) The fact that I am so born might generate a _reason_ for me to be treated in a certain reasonable way, i.e., not getting punched or verbally abused. Call this the _nativist claim_.

Now, (i) is clearly able to do a lot of work in explaining why I would give the Reply. I think it would be quite acceptable for me to do a whole host of actions in order to avoid getting punched or abused, regardless of spouting sophistries in the public square. But is (i) all that we can say to justify giving the Reply, or to justify the ruffian's reaction to it?

I would like to hear y'all's thoughts on the matter. But to end, and to hint: my view is that being born here, rather than there, does not generate any additional reason to be treated in some way; rather, it is a fact which generates a reason to dismiss a forseen objection to being treated in some way. And: what's operative in the Germany example is, not that being born in Germany matters, but rather that differences in punishment should depend not at all on facts about birth. The reasons why the "right of blood" is bad don't make the "right of birth" good; they're both bad, but for non-co-extensive sets of reasons.

(I've made a change in the sections on Germany; I had accidentally switched traits about who was non-German-born.)

2 comments:

I imagine that the 'but he was born and raised here' response in the Germany example seems like a good one to people because of the latter half: if someone has lived in a community her entire life, that gives one very strong reasons not to forcibly uproot and expel her. Birthplace is a separate and irrelevant consideration, as I see it. To claim that someone who was born in Mexico and then grew up in the US has a weaker claim to the benefits of US citizenship than someone who was born here and then grew up elsewhere and that US policy should reflect those claims strikes me as utterly implausible, and I would enjoy hearing someone try to argue for it (explicitly).

Since the birth-based citizenship criterion is more likely to coincide with the non-arbitrary fact of where one has lived one's life than the blood-based criterion (and perhaps a little less likely to encourage ethnic nationalism?), it strikes me as better.

I think that I agree with Sean entirely. But I want to stress that, while the uprooting of the German-born Turk is especially harmful, and so in need of strong justification, one can see how a comparable amount of harm is felt by a non-German-born Turk who has friends, family, language, and culture all rooting him in his new, but no less pivotal, German homeland. This fact puts pressure on another implausible claim I'd like to see defended: that the non-German-born Turk has a weaker claim to citizenship rights than does a German-born Turk who has lived his entire life in Germany. For Sean's example pits birthplace against a life's attachments other than birthplace. But I also want to know what weight birthplace has at all, holding constant the factor of "life's attachments." Sean clearly agrees, I think, with my point here, by virtue of his claim of birthplace as an "irrelevant consideration." But I just want to point out that, in Sean's example, I am skeptical of the claim that the Mexican-born resident has either weaker or even equivalently strong claims as does the American-born expatriate.

Let me flesh out my hint: What function birthplace serves is that it answers a kind of objection to fair treatment, not just in the sense of harms that Sean mentioned. When I tell the South Boston Bully that I was American-born, my point, partially, is to say: You view me as a threat because I am different; but the fact that I was born (or born-and-raised) here underscores a similarity which you should take as evidence of my not being a threat to the nation. Now, this is not to say that my being American-born entitles me to a certain special treatment; it is just an answer to a claim about how I should be differently treated. Something similar can be rightly said by, say, Japanese-Americans: "That my family has lived in America for three generations provides you, FDR, with evidence that our aims are probably not orthogonal to yours."

Post a Comment